The future of villages lies in the hands of rural activators

“One of the critical objectives of current EU policy is to maintain lively rural areas. Rural activators are the only ones able to change these areas' fate. However, the desire to restore the rural areas should lay to all of us since we benefit from it. Rural activators face various socio‑economic pressures that make their work hard to maintain.” Justyna Turek, CEO of HOLIS, looks into a possible future for rural life.

“One of the critical objectives of current EU policy is to maintain lively rural areas. Rural activators are the only ones able to change these areas' fate. However, the desire to restore the rural areas should lay to all of us since we benefit from it. Rural activators face various socio‑economic pressures that make their work hard to maintain.” Justyna Turek, CEO of HOLIS, looks into a possible future for rural life.

By Justyna Turek, CEO of Holis

Photo: Bianca Ackermann/Unsplash

Around 30% of the EU's population lives in rural areas. Between 2020 and 2030, rural populations are projected to increase by only 1 per cent, compared with 8 percent in urban areas, which means that rural areas will continue facing their already existing challenges like demographic changes, poverty, and a lack of access to basic facilities. These regions risk their inhabitants abandoning the villages, and those who remain don't have adequate tools to regain their agency or rebuild interest in this place. In 2021, the European Commission adopted its communication "A long-term vision for the EU's rural areas – Towards stronger, connected, resilient and prosperous rural areas by 2040". This apparent need to support the rural activators so the rural region can flourish caused the beginning of the project Open School for Village Hosts (founded by Erasmus+).

“Rural areas are the fabric of our society and the heartbeat of our economy. They are a core part of our identity and our economic potential. We will cherish and preserve our rural areas and invest in their future”– Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission.

It's never the people's problems. It's a situation problem. Holis has marked all the projects we have been working on with this approach. It became incredibly relevant at the Open School for Village Host project since, to reverse the system (situation), we need to support the people first. The rural activists need the most attention, not yet another house to build or a highway to make. Through this project, we want to build agency within the people and the community by investing in them. Rural activators with the right tools can change the situation/system more than outsiders, who often do not know the context and community.

Holis, together with other partners, aims to support and train rural activators through an innovative training program that proposes creating a new core of competencies that benefits European villages. With this project, we also aim "do our part" (The Flight of the Hummingbird story) and reverse (or at least try!) global issue as rural depopulation step by step. Rural depopulation affects regions where the rural exodus outstrips natural growth, reducing the total number of inhabitants to a critical level and causing the ageing of demographic structures. The Shrinking Rural Regions policy brief shows that Europe's demography became a significant policy challenge. A shrinking population has become the typical course for numerous rural regions as agriculture is restructured and the population (especially employment) moves to urban areas.

We stumbled upon this topic with Holis' participants at Holis Summer School in 2019, where we worked on revitalising economic and social fabrics in the Odemira region, Portugal. Then we discovered the depth of this challenge and got close to the rural activators who were almost willing to fight for their villages to stay alive. Small villages around Europe and the world suffer from accompanying problems that often are inseparable from depopulation. The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic amplified it even more. For example, in America, the effects of the pandemic on rural populations cause unemployment, downsized life satisfaction, and cause serious mental health problems, not to mention the economic outlook.

Nevertheless, several social and rural enterprises are already generating positive social impact in those areas, changing the rural regions' perspective and future. A common feature in all these positive experiences is a skilled person based in the community, who identifies opportunities, connects local actors, and continuously develops projects. Such superheroes are already existing and might recognise them (article about the rural activators). Although the description of a rural activator, called a 'Village Host' for this project is new, local and regional work is already being done by local pioneers, social innovators, and enterprising local officials.

We believe that the rural regions' future is not yet decided. We believe that the future lies in the hands of these rural activators. By supporting them, we give them the right tools to sustain the development of the villages and the regions. At the same time, we will be able to promote a new economic model to be potentially applied to all inner areas and small villages of Europe that will foster social innovation, inclusion and valorization of local heritage. The most relevant aspect is the sustainability and transferability of the identified cooperation model and training solutions. Open School for Village Hosts project seek to reach out to adjacent projects in Europe and beyond whose work and expertise overlap with ours.

"Village Hosts bring new social, economic and ecological life to small villages and their local economy. In terms of public policy, the Open School for Village Hosts creates 'public goods in the form of social cohesion, public health, territorial development, food sovereignty, farmer livelihoods, learning, innovation, and biodiversity" - John Thackara, the expert supporting the program.

What's next? Holis and Open School for Village Hosts partners have been busy for the last couple of months. We have been researching, collecting data, and conducting focus groups and interviews with experts o capacity building, the future of the skills and rural development. Now, we are creating a test training module out of these findings that will be used to teach rural activators new skills. At the end of 2023, we aim to deliver outcomes as a practical platform, handbook, manifesto, and additional materials to support Village Hosts' development. What is most important in this work is remembering the human element, which is crucial here to make this program succeed. To do it, we invite you - dear readers and Holis supporters - to provide us with your feedback, knowledge or/and opinion on this topic. Maybe you know an already existing rural activator? If yes, please put us in contact.

The partners of the program: Casa Netural, Materahub, ELISAVA University School of Design and Engineering of Barcelona, CDOP, Radošā partnerība, KobieTy Łódź and We Are Holis. Special advisor John Thackara

Photo: John Fornander/Unsplash

Putting Soul Into Planning And Design

“Places need to be the armature of planning and design. And we can’t just concentrate on filling those places. We must put people first in planning and design instead of building cities that erase all that is meaningful about the places in which they exist and the people who call those places home.” Phil Myrick, global placemaking leader, wonders why new development often treat humans as an inconvenience.

“Places need to be the armature of planning and design. And we can’t just concentrate on filling those places. We must put people first in planning and design instead of building cities that erase all that is meaningful about the places in which they exist and the people who call those places home.” Phil Myrick, global placemaking leader, wonders why new development often treat humans as an inconvenience.

By Phil Myrick, global placemaking leader

Photo: Mishal Ibrahim/Unsplash

When we move into a new home, what’s the first thing we do?

We make it our own.

Whether it’s furniture, paint, art, or lawn ornaments, humans are hardwired to personalize the places in which we live. To differentiate them from those of our neighbors. To create a place in which we feel good. To make them a home.

The question then is why does this so rarely translate to the design of our cities and neighborhoods? Why do we have to fight for ourselves as humans for the public places in which we can feel alive? Why is the city building process so normalized to scraping clean every artifact that makes us feel good and replacing it with big, boring, uniform rectangles?

We wouldn’t tolerate it in our homes. Why has it become the default for our cities?

Places first, boxes second

Humans are creatures and like every other creature they look for habitats in which they feel comfort and nourishment. In our cities, that often translates to public spaces in which they can feel good.

And studies have shown how, when we feel more attached to our neighborhoods, we’re more likely to invest our time and money there.

Too often, though, the creation of places seems to be approached from the wrong direction. Instead of prioritizing places that foster life and engage our senses, urban development proceeds relentlessly in favor of building nothing but boxes, maximized on every block, as if humans were an inconvenience that should make their way around them.

The process is more about filling space than creating place. You and I become the last priority.

Places need to be the armature of planning and design. And we can’t just concentrate on filling those places. We must put people first in planning and design instead of building cities that erase all that is meaningful about the places in which they exist and the people who call those places home.

Case in Point

You can see evidence of how not to do it all over our cities.

I was in Austin recently and was appalled at how streets that have been surrendered to soulless rectangles - domineering buildings that erase all comfort for the human being. The building of boxes had taken over all other considerations. Yet, nearby, on the University of Texas campus, you see people socializing and lounging in beautiful, comfortable spaces.

Why do we have to scramble our way through cities searching, often in vain, to find these vibrant places instead of using them as a central armature and planning around that armature?

Or look at Kendall Square in Cambridge, MA, an “innovation district” that has been built up over the last 30 years, one of the world’s greatest concentrations of smart people. Approximately 100 acres of Cambridge, one of the most livable cities on earth, has been removed from human circulation and turned over to impersonal rectangles. I honestly don’t get it - can’t we do urban economic development and build places where people feel human all at the same time?

People move to attractive, vibrant places where people are welcoming and friendly. Put simply, high-performing habitats = high-performing cities.

So, how do we achieve those high-performing habitats as opposed to just talking about them?

Turn the development process around. Start by defining a framework of high quality places where people will spend their time in public – for recreation, shopping, dining, relaxing, socializing. Connect those places to each other through walkable environments, and then plan and design buildings that integrate into these community hubs. Put another way, start by creating a placemaking framework plan.

You’ve got to build a place that speaks to people - a place that builds the soul of a community as opposed to erasing it.

Photo: Zhaoli Jin/Unsplash

Profound Play - Why Play, Not Hard Work, Is The Key To Creating A Better World

“This essay attempts to debunk a common myth: creating a better world requires hard work. It argues that the most effective way to change our world is through play. Not just any kind of play – profound play. As you are about to discover, the great tragedy in our culture is that we have lost sight of the enormous, creative, transformative power of play. We have trivialized it as something we outgrow as we transition from childhood into adulthood.” David Engwicht, CEO of Creative Communities International.

“This essay attempts to debunk a common myth: creating a better world requires hard work. It argues that the most effective way to change our world is through play. Not just any kind of play – profound play. As you are about to discover, the great tragedy in our culture is that we have lost sight of the enormous, creative, transformative power of play. We have trivialized it as something we outgrow as we transition from childhood into adulthood.” David Engwicht, CEO of Creative Communities International.

By David Engwicht, CEO of Creative Communities International

Photo: Pablo Pacheco/Unsplash

The evolutionary drive to play

Brian La Doone watched in horror as a very hungry polar bear lumbered towards Hudson, his sled dog chained to a post. It was November and the polar bear had not eaten for months. Hudson was an instant dinner served on a platter.

But Hudson did not panic or try to escape. Instead he behaved as if he wanted to play by bowing and wagging his tail. The bear responded to the invite, and the pair had a playful romp in the snow. After fifteen minutes the bear lumbered off.

The next day the bear returned about the same time for another frolic with his new friend. On the third day, Brian La Doone’s workmates gathered to watch the play-date. The play dates continued for a week, by which time the ice had thickened enough for the bear to go hunting for a seal.

Stuart Brown, in his book Play (Scribe 2010), asks the question, why was play more important to this bear than a meal?

Scientists have become intrigued about play in the animal kingdom, and the role it plays in the evolutionary process. Adult ravens have been seen sliding down a snowy slope on their backs, hopping up, flying to the top, then sliding down again. Bison have been observed running onto a frozen lake, and skating along on all fours while trumpeting wildly. Octopuses play. It even appears that ants play. If play is just ‘for fun’ and serves no useful purpose why is it so widespread in nature? If it is a non-productive activity (a waste of energy), why has it not been eliminated by the evolutionary process that only rewards characteristics that give an organism a competitive advantage? Surely animals that are playing are an easier target for a predator than those giving serious attention to their environment? Wouldn’t polar bears that eat sled dogs have a better chance of survival than those that choose to play with them?

To find an answer to this question, Dr. Stuart Brown spent some time with Bob Fagen, an expert in animal play. For fifteen years Bob Fagen had been studying the behaviour of grizzly bears in Alaska. Dr. Brown found himself thirty feet up an old cypress tree with Fagen watching grizzly bears at play. Fagen explained that what he had documented after years of observation was that ‘the bears that played the most were the ones that survived best’. He explained why, ‘In a world continuously presenting unique challenges and ambiguity, play prepares these bears for an evolving planet.’ In other words, play is not just for fun. It builds resilience and increases the chances of survivability. So evolution rewards the animals that play the hardest.

In fact, play does more than merely improve the chances of surviving. It builds bigger brains. Scientists now understand that when we play, we create new networks in our brain. Rats in a play-rich environment grow bigger brains than rats deprived of opportunities to play. Play makes us smarter. Dr. Brown says that when kittens stage mock battles with each other they ‘are learning what Daniel Goleman calls emotional intelligence – the ability to perceive others’ emotional state and to adopt an appropriate response’. Play stimulates the development of the brain’s frontal cortex, the part of our brain responsible for cognition – which entails sorting relevant information from irrelevant information, monitoring our thoughts and feelings and planning for the future.

Play allows us to experiment with the future, to test out potential scenarios in a non-threatening, non-critical environment. Which is why in nature the strongest players are the strongest survivors. In his book, Deep Survival (W. W. Norton & Company, 2017), Laurence Gonzales, looks at why some people survive while others perish in a life and death situation. One of his surprising findings is that the adults who have forgotten how to play are the first to perish.

They have lost the flexibility to play with potential scenarios and solutions in their head. Their thinking has become rigid, and they die.

At the most fundamental level, without play we have no capacity to imagine and plan for a future that is different to today. It is literally how the child we once were built the adult that we are now. In play we created thousands of potential futures, then stepped into those that most appealed to us. Play, not hard work, is how our whole civilization was built. Without the ability to create potential futures in our brain, there would be nothing to build. Changing our destiny, or the destiny of our culture, requires that we relearn how to play again. Hard work will simply not do it.

The great demise of play

It is a biological fact that the brain of a child is different to the brain of an adult. In fact the human brain is still building itself up till our late teens. This period of ‘biological immaturity’ is universal. But the underlying story we tell about this period changes dramatically from one era to another, from one culture to another, and even between different classes in society.

However, the scientific and industrial revolutions dramatically changed the underlying story we tell about the meaning of childhood, because they altered the underlying story we tell about the meaning of adulthood. For thousands of years people had defined their identity by their relationships - the tribe to which they belonged, their family of origin, and the location where they lived. The first question you would ask a person in order to establish their identity was, ‘What tribe do you belong to?’ But the scientific and industrial revolution changed this. We began viewing the universe, including ourselves, in machine terms. People began to define their identity in terms of what they produced as a productive ‘machine’ in society. The first question to establish a person’s identity became, ‘What work do you do?’ Or decoded, ‘As a productive machine, what products roll off the end of your production line?’

This change in conception of identity for adults had significant impacts on how adults viewed the identity of children. When identity was tied to a person’s relationship to place and people, children were able to share this adult sense of identity. Children were ‘little adults growing into big adults’ sharing the same tribe and the same connection to locality as the big adults. But when adult identity became tied to what the adult produced as a productive machine, children were unable to share this new adult identity (well certainly not after child labour laws banned children from the workforce). A new way of conceiving of childhood needed to be found. There are many writers who argue that there was no concept of childhood prior to the scientific and industrial revolutions. Whether this is correct or not is immaterial. What is important is that after the industrial revolution, the concept of childhood carried within it the notion that this is a period which is very distinct and of an entirely different nature to adulthood. Childhood was now conceived as an apprenticeship for adulthood. To be grown up meant to shed our childhood as one sheds clothes that are outgrown. This journey to adulthood is a linear journey. Children work their way through grades at school, learning the skills needed to be a productive ‘machine’. Along the way adults tell the children to ‘grow up’ and ‘stop playing around’. And the adults ask the children over and over, ‘What do you want to do when you grow up (become a productive ‘machine’)?’

This viewing of our identity through the machine-model prism not only changed the way we view childhood, it created an artificial distinction between work and play. The high value we place on work – based in the good old Protestant work ethic – means that we view the real work in our society as being done by adults. Yet children are perhaps doing the most serious and creative work of anyone. They are in the process of inventing and creating a sophisticated, mature, rational adult – and they are doing this important work through dream, play and fantasy. The distinction between work and play is therefore totally arbitrary. In fact, (as I will explain later) what is play for one person is work for another and what is work for one person is play for another.

Because our culture values ‘serious work’ over play and sees serious work as belonging to adulthood, we have totally undervalued ‘serious play’ and therefore downgraded the importance of childhood.

If a society values the work of adults over the play of children, and sees these as separate worlds, then this will manifest itself in the way space is arranged in our towns and cities. Segregated and specialized areas will be created for children’s play. Play and the activity of children will not be integrated into adult space and therefore child’s play will not intersect with the serious activities of the adult world. Traditionally, the space where children’s play and the adult world intersected was the street. But in our culture the street has become the exclusive province of ‘productive adults’ in machines that improve the adult’s efficiency. Instead of the street being the premier play space for children, we have created segregated and specialised play grounds. This segregation of the child’s world from the adult world in our urban form is no accident. It is a reflection of our deep-seated stories about childhood, and the trivialising of play.

Photo: Greg Rosenke/Unsplash

What is work and what is play?

What is work for one person can be play for another. For a child, washing up may be a game while for an adult it is work. So whether an activity is play or work is determined by our mental attitude, not by the nature of the activity. At any moment each of us has the power to transform play into work… or work into play. Even the most serious work, like making a better world, can be turned into play. As we shall see, ultimately play is the only way to make a better world.

Play is transformed into work when we take a game, or our role in that game, too seriously. Work is play stripped of its playfulness. Play can also become work if we are forced into playing a game we do not want to play. (Technically this is slavery, not work.) But as we shall explore shortly, even slavery can be transformed into a game. Many a slave feigned acceptance of their humiliations, playing a role so the master could live under the illusion that it was he that was in charge. A favorite proverb of the Jamaican slaves was, ‘Play fool, to catch wise’.

It is the contention of this short book that creating a better world, in fact all of life, is meant to be a playful game. Activities only become work (or in many cases slavery) when we strip them of their playful element. A common element of both work and slavery is a feeling of entrapment and loss of freedom. In play you can be whatever you want to be, but in work or slavery you are locked into a single role and you feel forced to play out this role.

Most social activism is a revolt against ‘the system’ that demands the game be played according to certain rules – rules that we find unjust or unfair. Ironically, these social activists take on a stereo-typical role as people ‘working for change’. They often become just as trapped in their particular role of ‘social activist’ as those playing roles in the ‘establishment game’. These social activists allow themselves to become enslaved to the rules of the working-for-change game. They lose sight of the fact that the very essence of freedom is the ability to transcend the rules of the game simply by starting to play a different game. The entire universe would be enslaved to blind determinism if it were not for play.

Real change happens automatically when we change the rules of the game, our role in that game, or simply invent a new game.

Now many people will have great difficulty with this notion that all of life is really a game. But being a ‘rational adult’ is just a role we have invented, and that we inhabit from time to time (or for some, a majority of the time). It is a game that is governed by a different set of rules than when we play other roles, such as jester, or wise old elder, or lover, or playful child. Even though our role as ‘rational adult’ seems more serious than some of our other roles, at its core it is still just a role in a game.

Whether you are wrestling with difficulties in a relationship, or a problem in the workplace, or a thorny social issue, if it has become ‘hard work’, the most transformative thing you can do is change your relationship to the situation by ceasing to see it as ‘work’ and viewing it as a ‘game’.

We are now going to look at six types of play: ritual play, role play, recreational play, letting-off-steam play, freedom play, and escapist play. These categories overlap, blur and merge and are not an exhaustive list. But what we are going to look at is how each of these types of play can be tapped into by the adult who wants to develop their skills in ‘profound play’ – the ability to combine play with wisdom.

Ritual play

One of the earliest types of play that we humans engage in is ritual play, for example the game of peek-a-boo where the adults pretends to hide behind their hands then reveal their face and says ‘boo’. Part of the nature of this game is repetition. It won’t work if you only do it once. The game is an early form of ritual play.

Why does the child laugh the longer this game goes on? In the first few months of life, this child endured a recurring painful experience: the mother they depended on for their very life would periodically disappear. This terror would subside when their mother returned, only to be rekindled when the mother left yet again. But through the game of peek-a-boo the child learns a very valuable lesson: my mother is always there, even when I can’t see her. This brings a certain comfort to the child to know that the person they depend on for life will always return. The ‘disappearing’ and ‘returning’ is ritualized into a game, and through the game the child learns to control their fears. When the parent puts their face behind their hands, tension rises in the child, for this part of the ritual reminds them of the fear the feel each time the parent disappears in reality. The pulling away of the hands brings the parent back, and releases the tension. This release of tension is reinforced by the parent pretending to give the child a fright by going ‘boo’. This ritual raising and releasing of tension is pleasurable and results in laughter. Part of the pleasure is also the paradox in this game: in play, the parent is not there; in reality, they are. The other paradox is that the parent pretends to frighten the child even though the child knows full well what happens next.

The entire rise of human culture is built on ritual. Even before we humans had a language to express our emotions and fears, we had rituals. Rituals to celebrate the changing of seasons, rituals to deal with life and death. Haunted by our dreams and the seeming chaos of the world around us, we were driven to create meaning as a way of allaying our fears. Like the game of peek-a-boo, these rituals gave meaning to the universe and provided a sense of comfort. The meaning-making inherent in rituals eventually gave rise to religion, the arts, civilization, and the sciences.

One of the endearing features of children is their ability to invent rituals, then let go of them once they have outlived their purpose. There is a time we stop playing peek-a-boo and move onto some other form of ritualized play. When I talk of ‘rituals’ I am not just talking about religious or spiritual rituals. Almost all of life is ritualized play. Meeting your family for lunch every Sunday is a form of ritual play. So is watching the footy every Saturday night, or buying the latest tech gadget. These rituals, and the rules related to these rituals, form the ‘culture’ of a civilization, community, workplace or household. Often these culturally-specific rituals have evolved over a long time, and those who want to get ahead ‘play by the rules’ inherent in the ritual.

However, much of the ritual in our culture has outgrown its usefulness. Yet as a culture and society we find it much more difficult to give up rituals that have outgrown their usefulness than we did as children. One reason ‘rational’ adults find it much harder to let go of their rituals is because the adult builds a rational reason for why they play the game. (As an adult it is compulsory to have a reason for your rituals.) The adult legitimizes their rituals with intellectual constructs which continue supporting the ritual long after it has served its useful purpose. Kids are therefore much more ‘rational’ about their rituals than adults. Or to put it another way, adult ritual is marked by a high degree of irrationality.

In the past, social change agents have thought that the only way you get a society to change its outdated ritual games is to first dismantle the intellectual constructs that support the ritual.

What these change agents failed to recognize is that the rituals are first and foremost an act of ‘meaning making’. Rituals are invented to give meaning to a chaotic universe, to anchor the soul. The attachment to the ritual game (such as owning a gun in the USA) is not intellectual but emotional. It is therefore virtually impossible to convince people to change their rituals by attacking the intellectual constructs used to justify the ritual. If we do not offer them a more meaningful ritual to replace the old, we are simply cutting them loose on a dark and turbulent sea.

Deep social change can only take place if change agents understand the role of ritual in imparting a sense of meaning. The job of the social-change agent is to give people the confidence to let go of their outdated rituals and to invent more meaningful rituals. This is not an intellectual process. The child lets go of their outdated rituals because they have an implicit belief in their creative abilities to invent new games and rituals.

Profound play understands that one way to produce significant social and cultural change is to introduce new rituals that paradoxically both anchor the soul yet at the same time set it free on a new voyage of discovery. Profound play does not overtly attack the rationality of current rituals nor the intellectual constructs that supports them. It simply offers the child in all of us a ‘new toy’. (Being ‘rational’ adults, we will always find a post hoc rationalization as to why we decided to play the new game!)

Role play

When most people think of role play they think of a theatre technique often used in small group work and therapy. However, this is a formalized version of role-play. Role-play is common across much of the animal kingdom. Baby cubs stage mock battles, honing their hunting skills for when they become independent and need these skills in the ‘real’ world. For children, playing shop, fire chief or baker is a way of trying on potential future roles like play clothes and seeing which ones fit best. Through role-play, children invent the rational adult they are yet to become.

There is no reason why tapping the creative power of role-play should stop when we reach adulthood. Through role-play we can experiment with roles we would like to play in the tomorrow we are creating together. In fact, role-play is the only way we have of visiting the future.

Role play has incredible creative power, and is a major tool in what I call profound play. Role play delivers at least four major benefits.

Benefit 1: Return of Innocence

When we play a role, we forget for a moment who we are and we are ‘born anew’ as someone different. This is the state of innocence which is fundamental to the creative abilities of children. Their mind is not cluttered with ready-made answers. They don’t need to learn how to ‘think outside the box’.

There is no ‘box’ to think outside – not yet anyway.

In 1987 I attended a public meeting to discuss plans to ‘upgrade’ a major road through my neighbourhood in Brisbane, Australia. I left the meeting a committee member of Citizens Against Route Twenty (CART). A week later I found myself media spokesperson, with no previous experience in community activism; no formal education; totally ignorant about traffic and urban planning; and utterly politically naive.

Full of incredible optimism, I started my new job with a six-hour door-knock along the proposed route. Every door I knocked on I got the same message: ‘Once they (the Bjelke Peterson Government) have decided to do something, there is nothing you are going to do to change it.’ I was stunned by this sense of resignation and powerlessness. Even our committee didn’t believe we could win. ‘We will give them a good fight,’ I was told, ‘but we can’t win.’ I was probably the only one in our entire community naive enough to believe we could win.

The reason for this pessimism was that the Bjelke Peterson Government had been in power for over 20 years and ruled via a giant gerrymander. They could do what they liked in the big cities because they only relied on the country vote to stay in power.

I had no idea what to do. Out of sheer desperation I suggested to the committee that we spend a half-day pretending we had won. I suggested we make up stories about how we won. That day we invented a whole lot of stories. One seemed more pregnant with possibilities than the others, so we decided to build our campaign strategy on this story.

Three years later we won, and it happened largely according to the plot framework of the story that we had created three years earlier when we played ‘lets pretend’.

Prior to playing ‘lets pretend’, our minds were shackled by the perceived wisdom that our community was powerless to change any decision made by the Bjelke Peterson government. By pretending we were victors, and seriously playing the role, we cleared the dominant story from the slate of our minds.

Part of ‘profound play’ is a robust intellectual understanding of issues. Paradoxically, it is impossible to gain this robust intellectual understanding without first ‘forgetting’ everything you know and returning to a state of innocence. For example, my second book revolutionized thinking on transport by asking the kinds of questions a kid would ask: ‘But why do we build cities?’ ‘But why do we have a transport system?’ It is only by asking these child-like questions that we can step outside the bounds of current knowledge. By putting ourselves in our child persona, or by putting ourselves in other people’s shoes, we are able to recapture this sense of innocence, but innocence that is informed by reason and wisdom.

Benefit 2: Experiencing of multiple-worlds simultaneously

The most productive regions in nature, from an evolutionary perspective, is ‘marginal t territory’ – the space where eco-systems meet and overlap, for example, tidal mud flats which are neither land or sea, but both. It is here that new life-forms evolve.

I was once asked to chair a meeting in Calgary, Canada, in which a group of residents were in conflict with their city council. So I asked the residents to play the role of city engineer and for the city engineer to play the role of residents. Before starting this role play, I asked the residents to train the city engineer on how to be good residents and I asked the city engineer to train the residents on how to be a good city engineer (Council bureaucrat). We then launched into the role play and the city engineer (now playing the role of resident) got in the face of the residents (now playing the role of city engineer) wagged his finger and yelled, ‘I first approached the city 14 years ago about this problem, and what have you done? Nothing! A big fat nothing…” The whole room erupted in laughter. Within two hours we had an agreed solution to a problem that had festered for fourteen years.

The reason we found a solution so quickly is rather simple. Every resident in Calgary has the potential to become a bureaucrat working for a Council. In a sense they already have a bureaucrat living in their head. And every Council bureaucrat is already a resident. The problem between the residents and bureaucrats had arisen because both had taken their adopted role too seriously. But through the role-play I got them to play two roles simultaneously – in ‘real life’ they may be a resident, but in the role play they were a bureaucrat. This meant that they were experiencing two worlds simultaneously and where these two worlds met was marginal territory, rich in possibilities. The collision of two worlds in a person’s brain always causes a new synthesis – a creative way to handle the tension between the competing worlds. While the world’s are kept separate, there is no chance for this new synthesis.

I often wonder if international peace negotiators take their work too seriously. What would happen in the Israel/Palestine conflict if all those at the table had to role play their ‘enemy’? What about the conflict between Councilors in local government. Imagine this. Prior to a Council meeting beginning, all the little wooden plaques, that sit in front of each Councilor and bear their names, are put in a sack. At the start of the meeting each Councilor has a lucky dip. They place the name they draw out in front of them. Then for the rest of the meeting they must argue from that person’s perspective (including adopting their mannerisms). Imagine how much more productive this would be than each arguing from their entrenched position.

The only way to experience multiple worlds like this is through role play, whether enacted in physical space or in our imagination. Profound play allows multiple worlds to co-exist and overlap, even if this results in conflict.

Benefit 3: Self reflection

Playing roles is not just a method of getting inside other people’s skins. It is a method of getting inside your own skin (or more correctly ‘skins’). Some years ago I went to a counselor deeply perplexed about why, under certain circumstances, I acted ‘out of character’. It was if I could watch myself changing from being warm and charming to acting like a cold rock. The counselor took two empty chairs and told me to imagine that in one sat Charming Charlie (the nice guy) and in the other sat Stonewall (the not so nice guy that seemed to like sabotaging the nice guy). I had to sit on the chairs in turn and conduct a conversation between these two characters. It was only a game. But through this role play I was able to get inside the skin of these two characters who lived inside my head and find out what made each of them tick. I was able to negotiate a ‘peace deal’ that allowed them to coexist in my head without them constantly sabotaging each other.

In a similar way, the culture of any society is driven by deep ‘subterranean psycho dramas’. Just as individuals have a cast of hundreds in their heads, many with contradictory needs and desires, so society has a cast of hundreds in their collective psyche. You cannot understand something like the gun culture in the USA (or any other seemingly irrational behaviour by a whole group of people) without understanding this hidden drama. Often the only way of understanding this is to get inside the skin of the cast members. Until you do, you are dealing only with the surface issues. Through profound play, we can bring these characters out of the murky underworld and get them to play in broad daylight. Through play we can explore new ways for them to relate to each other.

Through profound play, we can bring these characters out of the murky underworld and get them to play in broad daylight.

Benefit 4: Ability to reinvent ourselves

Children can reinvent themselves a hundred times in a single day. One moment they are a stuntman flying a biplane, the next a doctor, the next a cowgirl riding a bucking bull, the next a kangaroo. Yet there comes a point where we feel compelled as emerging adults to choose a very well defined ‘role’. (We are allowed more than one role, but we must project a consistent, singular role to each of the social grouping that we are a part of.) We begin to live under the illusion that these ‘roles’ are ‘the real us’. Worse still, we begin to judge others by the external roles they have chosen. But we are not our roles. We are still the infinitely creative child we once were, now playing a protracted role invented by that child.

Given half a chance, that child would still like to experiment with some new roles.

Photo: Rahmat Taufiq/Unsplash

Recreational play

Recreational play is what most people think of when I talk of adults playing. The concept of recreational play is built on a notion of a clear divide between ‘work’ and ‘play’. Work wears you out, and recreational play ‘recharges the batteries’. Only those who have worked really hard deserve recreational play. Recreational play is where you ‘enjoy the fruits of your labor’.

However, also embedded in this concept of recreational play is the notion that there is an underlying purpose for being refreshed and re-created. It is so you can get back to the serious business of life with renewed vigor. Play is really a maintenance break for the work machine.

This view of play is deeply ingrained in much of Western culture as a result of the Protestant Work Ethic (or Puritan Work Ethic). Luther and the other reformers (particularly Calvin) argued that hard work and frugality were the fruits of godliness – how God judged whether you were a white sheep or a black sheep. Max Weber argued in 1904 that this doctrine laid the foundations for the entire capitalist system. People’s sense of self-worth is tied up in the work they do, and how hard they work.

The split between work and play – and the privileging of work over play – results in a trivializing of play. We have been indoctrinated with the belief that creating a better world is ‘work’ and play is something we are allowed to do when we have earned a rest. ‘Work’, by its very nature, is rational and structured. Yet as we saw when looking at ritual play, the things we must change to create a better world are not rational or based in intellectual constructs. You cannot change something like gun culture in the USA through hard work.

Profound play views work as ‘creative play’. It rejects the notion, implicit in recreational play, that play and work should be separate identities. However, profound play keeps a balance.

Creative play does wear the player out, which means we do need to ‘recreate’ so we can regain our strength to go back to playing hard.

Adventure play

Our first experiences of adventure play were as babies – exploring our bodies and discovering our toes. Then we tried walking. We then graduated to bigger adventures when we walked home from school for the first time. Our childhood play adventures probably included trying to fly by jumping off the roof. Failing at the attempt and ending up in hospital with a broken ankle increased the size of the adventure. We couldn’t wait to tell our friends about the nurses in starched uniforms or the mushy food we were forced to eat. Later in life we climbed mountains, flew in biplanes, fought in wars, or drove fast cars.

There are four elements that distinguish adventure play from other forms of play: experimentation, risk, surprise and outcomes that etch themselves into our memory. An adventure is not an adventure unless it contains some experimentation and risk. Risk is dancing with danger and even death. It is a way of confronting our deepest fears and our eventual mortality and feeling mastery over them. It is paradoxical that those who play with death in their adventures probably take life more seriously that those who think life is too serious for play.

Adventure play can therefore be deadly serious. Ironically, this ‘dancing with death’ in play fills the player with a greater passion for life. It clarifies their vision. What seemed so necessary and essential in the serious work-a-day world suddenly appears as a trivial game. Confronting death and danger in the game moves the player from minor league to playing in the biggest game of all, the game of life.

In adventure play we are not necessarily looking for a successful outcome. The child who tries to fly by jumping off the roof and ends up in hospital is not disappointed because they failed to fly. In fact the pain and suffering they endure becomes an essential part of what constitutes the adventure. The outcome of the attempt to fly is a total surprise, and the nature of the surprise is what becomes etched into their memory as an adventure. In adulthood, this failed experiment will become a story which will be told at dinner parties and passed on to children and grandchildren. It will become a source of enjoyment and pleasure.

Serious world-changers are risk-takers who flirt with ‘failure’.

Profound play sees all of life as an adventure in which one must dance with death. Robert Neale suggests that it is possible for our entire life to become a ‘mature adventure which encompasses our entire existence’. This is the essence of profound play. It is a life-stance which defies ‘reality’. It is totally spontaneous in the way it responds to what unfolds during the journey. Failure or success are not the issue. Playing the game with flair and pizzazz is what matters. And by dancing with death there is an elevated feeling of walking with the divine.

Letting-off-steam play

This is closely related, but not the same as recreational play. In many cultures, festivals and carnivals were used as a way of giving expression to the ‘underbelly’ of the culture. For example, the Venice Carnival ran for over 2 months each year and was a city institution from the 13th century right through to the end of the 18th century. By wearing masks, participants were able to step outside social conventions and express different parts of themselves. At this time homosexuality was punishable by death. Yet during the festival a man wearing a Gnaga mask (a female face) was free to engage in flirting and sexual relations with men because he was only ‘playacting’. Kings, queens and important people from all over the world came to Venice to become anonymous and play out a range of repressed roles, from prostitute to fool.

In modern, Western culture this playing out of repressed roles has been largely limited to us passively and vicariously living out the roles through theatre, film and literature. Letting-off-steam play is essential to the overall well being of both individuals and a society, because it gives expression to those characters living in our head which we have suppressed.

In our culture we have a greater tendency to lock up parts of ourselves than in some other cultures. People who hold contradictory desires are considered to be mentally unwell. They are counseled to make up their mind about what they really want. However, the reality is that all of us have a whole lot of different ‘people’ living in our head, and many of these have conflicting needs and desires, and this is perfectly normal. Some days our introvert is in control and we don’t want to talk to anyone, while other days our extravert is in control and we want to talk to everyone. If we accept the notion that we must have a ‘single, unified identity’ then we are forced to lock-up the parts of ourselves that hold contradictory desires. Now something interesting happens when we do this. The part of ourselves that we lock up becomes increasingly frustrated and angry. It is inevitable that they will eventually erupt – often in an unhealthy way. This can lead to a Jackal and Hyde situation where we flip-flop between unhealthy extremes.

Choosing particular roles to play in ‘real life’ automatically means that other legitimate parts of ourselves can become neglected. In letting-off-steam play, we give expression to these suppressed parts of ourselves. By giving these parts of ourselves and our culture a space in which to express themselves, we stop them from festering in the basement and becoming destructive rogue elements. By making them our friends we draw their sting. And in celebrating them we suddenly find that we have freed ourselves of their negative power.

Profound play uses letting-off-steam play to make friends with the dark underbelly of culture and in making friends, draw the sting of these hidden elements. It also recognizes that our hidden demons come bearing wonderful gifts. In play, all demons are less scary than they are in ‘real’ life.

Photo: Leon Liu/Unsplash

Freedom play

This kind of play is epitomized by the Black American slaves in the cotton fields singing to ease the burden of their oppression. But this kind of play was more than just ‘pain relief’. It was an expression of inner freedom. They were saying, ‘You can chain my body but not my mind’. All meaningful play contains a deep paradox. The deeper the paradox, the greater the creative potential of that play. In freedom play we see this principle at work. In the real world they were slaves. In their play they were free. This bought to their play something deeply spiritual and creative. In fact their play was a reflection of ‘divine play’; the act of turning chaos into meaning, death into life, garbage into gold. This divine transformation could only happen in play.

In place making I often say to clients or communities, ‘your greatest deficit is potentially your greatest asset’. The worse something is, the more I rejoice, because it has the greatest potential for transformation. An example of this was the Maiki Hill toilets in Paihia. They were so bad some tourist had scrawled on the wall, “Worst toilets I have seen in NZ”. The community could only imagine bulldozing them and starting again. But for just $15,000 we transformed them into a tourist attraction. This approach to ‘deficits’ comes from an inner stance in my mind, rooted in freedom play. It is why I count my lack of education and the beatings I endured as a child as my greatest assets.

This kind of freedom play can liberate us from anything that oppresses us. If our past oppresses us, we can transform our past from something that oppresses us into something that enriches us. If our fear of death and non-being oppresses us, we can transform it something that gives our life color, vibrancy and depth. Profound play is the Jester in the universe who laughs in the face of death because she knows something death does not know. In an ironic twist she will conjure from the darkness something of substance. The joke is on death itself. Death cannot be reasoned with. So the Jester does not try. She simply plays, and laughs. And by laughing in the face of oppression she becomes master of the oppression. Freedom play enlists the ‘enemy’ as the agent of change.

Escapist play

When I talk about play most people think I am talking about either recreational play or what we may call ‘escapist play’ – play that is used to escape responsibilities or as a way of putting-off dealing with some issue or situation. Escapist play can sometimes have a self-destructive element, particularly when it is used as a pain analgesic – a means of escaping one’s internal demons. This kind of escapist play sometimes involves the use of drugs to further dull the pain.

However, not all escapist play is bad. We adults have a tendency to take ourselves, and the roles we play, far too seriously. When seriousness becomes our master, escapist play can restore the balance, and help us realize that even if the game we are playing has serious consequences, at the end of the day, it is still a game.

For the profound player, escapist play can be a time when the mind becomes a blank slate, much like when we go to sleep, and the dreaming part of our brain wanders where it wills. In these moments we may stumble on new cracks in reality which turn out to be doorways into worlds not yet dreamed of. Escapist play can suggest new games that can be taken back into the profound play state. Escapist play can unwittingly unmask inner demons we don’t even know exist.

There is also a great temptation for those involved in profound play (‘serious play’) to start taking themselves as seriously as those involved in ‘serious work’. In all of life there is a temptation to fundamentalism. For some people, ‘profound play’ will become the new religion, replete with new rituals that must be kept unadulterated. To the shallow profound player, escapist play will be condemned as a form of sacrilege. To the deep, profound player, it will be a sacrament. The issue here is balance.

When change become ‘Child’s Play’

The thing about children’s play is that for the most part it does not have a predetermined objective. We said that the miracle of life is that the child we once were invented the rational adult we now are. But when kid’s play shopkeeper or fireman they are not saying to each other: ‘Lets play shopkeepers so I can see if that is what I want to be when I grow up’. In fact the exact opposite is true. In play the child is usually captivated by the eternal now. Past and future are no consideration. This allows their play to unfold in a totally spontaneous fashion.

The play is not constrained by past failures or dictated by fears of the future. And yet out of this seemingly directionless activity they create whole new worlds.

This raises an interesting question: ‘Should play ever have an objective?’ There are some that argue that play that has an objective ceases to be play and becomes work. I disagree. All play has an objective, even if this is simply to have fun or embark on an adventure. However, the objective remains fluid and not static as it is in ‘work’. It responds instantly to the game itself, and can morph into directions that were not dreamed of.

Profound play can also have an objective, such as improving a relationship, or addressing a social issue. However, the objective remains eternally fluid. This requires an incredible faith in our own creative abilities. It is to look the universe in the eye and say: ‘Throw at me what you will, and I will weave it into my story. Throw at me disaster and I will not only weave it into my story, but I will use it to make the story even richer.’ What we adults call work is often an attempt to second-guess the future and to build defences against all possibilities. But this ‘rational’ approach to the future is highly ‘irrational’. We can no more second-guess the future than King Canute could hold back the tide. It is far more rational to reclaim the blind faith we had as children that we could ‘make up the game as we go’. As kids we did not sit in a corner, paralyzed by fear, because we didn’t know if we were capable of playing. We had an implicit trust that as events unfolded, we would be able to fold them into the game as it emerged.

However, reclaiming this child-like quality to play is not a case of just role-playing yourself as a child. It must not be viewed as some mental trick we use when we need to be more creative. ‘Oh, I need to be creative so I’ll slip down into the basement and drag my kid out.’ The child in our head must be integrated seamlessly into the very essence of our adult persona. You and the child must become one. That is profound play.

Some years ago, while I was travelling in Europe, I watched an old lady sitting on the side of her street shelling peas while her grandchild rode a trike in the street. Every now and then the child would come over and shell a few peas. I watched the child playing, and wondered what kind of adult they were in the process of creating through their play. I looked at the old lady. I imagined that being in the presence of the child helped her recall her own childhood, and the road she had travelled. By remembering, she was distilling wisdom from her life’s journey – wisdom she could pass to the child who was just starting their journey. The street is where these two worlds met and merged.

Profound play is where wisdom and play are allowed to share the same neural pathways in our mind. It is the child we once were in the presence of the wise elder we are becoming. This can be a partnership of immense and profound creative power.

Photo: Catarina Lopes/Unsplash

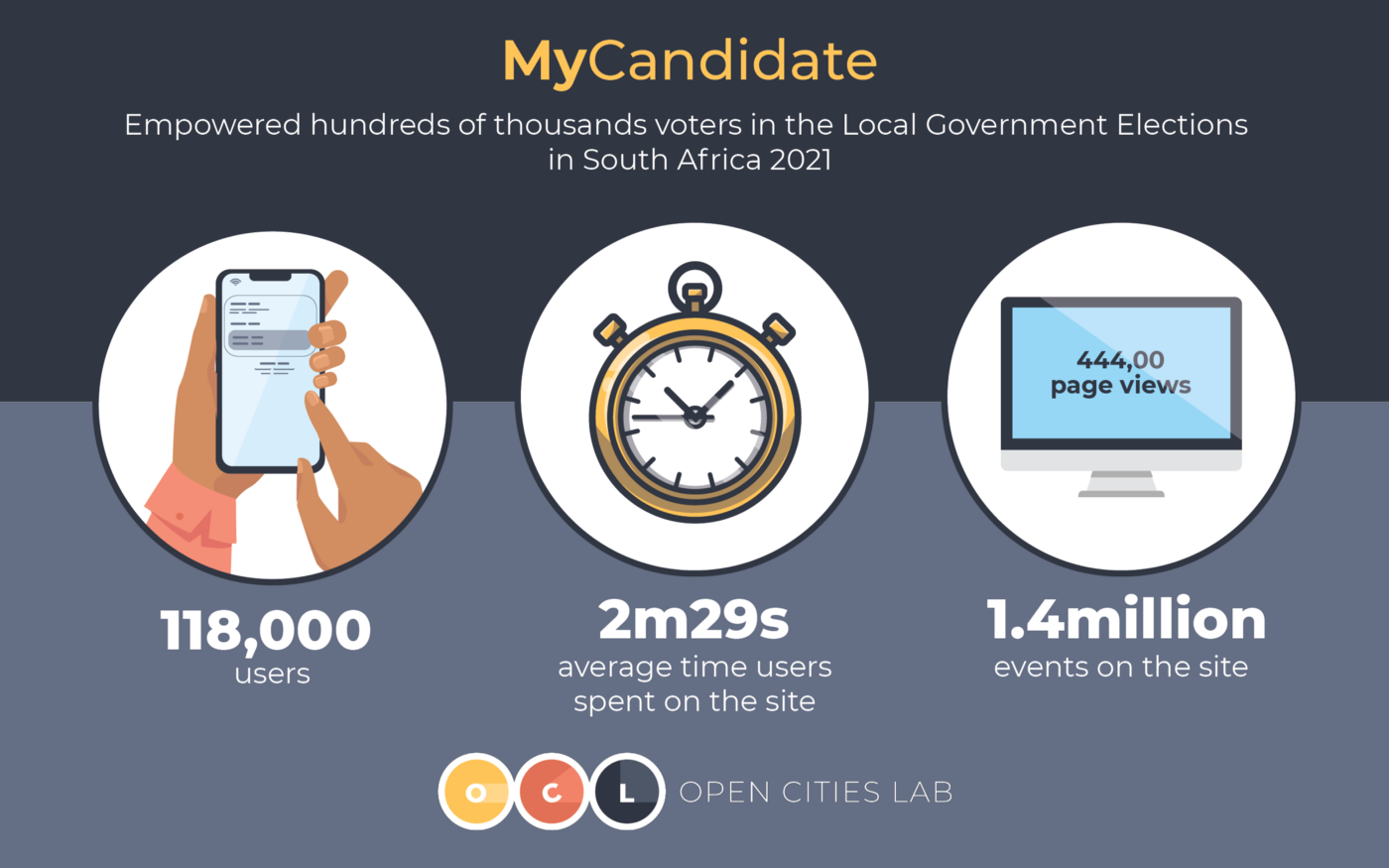

How One Piece Of Code Empowered Hundreds Of Thousands Voters In The South African Local Government Elections 2021

Open Cities Lab is using code to create social capital and civic engagement. “My one concern was that it was too simple to be useful,” said founder Richard Gevers. “Clearly it wasn’t and clearly this is something people wanted. If you create an enabling environment, people can and will participate.” This is how hundreds of thousands of voters were empowered in the South African 2021 local government elections.

Open Cities Lab is using code to create social capital and civic engagement. “My one concern was that it was too simple to be useful,” said founder Richard Gevers. “Clearly it wasn’t and clearly this is something people wanted. If you create an enabling environment, people can and will participate.” This is how hundreds of thousands of voters were empowered in the South African 2021 local government elections.

Photo: Element5/Unsplash

The founder of Open Cities Lab (OCL), Richard Gevers, was all over the South African press recently talking about mycandidate.opencitieslab.org — the tool that tells you who you can vote for in the Local Government Elections (LGE). It was only possible because the open data community made it happen. The portal is a collaboration between Richard Gevers (Open Cities Lab leader), Matthew Adendorff (head of Data Science at Open Cities Lab), Adi Eyal and JD Bothma (from OpenUp), Paul Berkowitz (who wrangled data from the IEC), Wasim Moosa (Open Cities Lab Lead developer) and Jodi Allemeier.

At the time of publishing, 118 000 people had used the tool, and we can assume that most of them were registered voters. And possibly more exciting than the site analytics are the stories about people who used the tool and as a result started engaging in conversations with their friends and peers about who their ward candidates were.

Illustration: Open Cities Lab

How it works: Type in your address and it will identify your ward as well as all the candidates contesting in your ward, as listed by the Electoral Commission of South Africa (IEC). Each candidate’s name, age and political party appear in the search results including all the other wards in which the candidate is contesting. When you click the name of the candidate, you will be redirected to the google search results for that name. You can also view more information about your ward by clicking the link to Wazimap.

Illustration: Open Cities Lab

It’s a really simple tool. “I really wasn’t sure if it would be successful,” said Richard Gevers. However the positive reception and media attention mycandidate.opencitieslab.org received proved that at least some people do want to have an active role in society. He said, “If you remove barriers, they can get involved. My one concern was that it was too simple to be useful. Clearly it wasn’t and clearly this is something people wanted. If you create an enabling environment, people can and will participate.” This is how hundreds of thousands of voters were empowered in the 2021 LGE.

How it all started: Just over 2 weeks before the LGE on 1 November 2021, Richard and a few colleagues were having dinner together, when one of OCL’s data scientists, expressed frustration with not knowing who to vote for. Th information about candidates was not easily accessible, even for our tech savvy team.

Amidst the end of the year rush to meet deadlines, Richard had asked Matthew Adendorff (Open Cities Lab lead data scientist), what it would take to get the MyCandidate tool up and running. Knowing that the data on each candidate was published by the IEC in pdf format, Matt was not sure if it was possible within such a short time frame to scrape all the candidate information into a spreadsheet and cross check it for accuracy. The data needed to be available in an open format.

It just so happened that Paul Berkowitz had just done this. With much effort, he had taken all the candidate information in the pdf and made it openly available on this google spreadsheet. So that night, Matt plugged in the now open data and resurrected the mycandidate.opencitieslab.org

It was far from perfect. There was no styling or even any branding but it worked. A few days later at 18:58 on 19 October 2021, Richard tweeted a message asking the twitter community for some user testing feedback. The responses were invaluable, and the retweets and media attention catapulted this simple tool into stardom.

The first version of the MyCandidate tool had been conceived and published just days before the 2016 LGE. The use case then was the same: Who are the candidates running in my ward? Some of us know about the parties contesting in our ward, but who are the candidates, and who are the independent candidates. Five years later, the tool went live in just enough time to reach a wider audience and have a significant impact.

All the hallmarks of Open Data:

The success and impact that the MyCandidate tool has had and will have in the future are testament to the Open Data Mission and the mission of Open Cities Lab: We work to build inclusion and participatory democracy in cities and urban spaces through empowering citizens, building trust and accountability in civic space, and capacitating government. When we can use technology and open data to do this, we do.

The MyCandidate tool is licensed under the Attribution 4.0 International. Leading up to the elections, we encouraged media organisations and even the IEC to embed the tool on their site. The embed code is available on the tool itself. We invite you to find, use, test, improve and share the code, which can be found on Github here.

Change Log:

Since the MyCandidate tool went live on 19 October 2021, some changes and improvements were made. Wasim Moosa (Open Cities Lab Lead developer), worked late on Friday night before the Monday election day, to solve the geocoding “problem” we had. It’s a wonderful problem to have so many users that the search functionality needs upgrading. When the number of users exceeded a certain threshold, Wasim needed to switch the geocoding query to google places API.

Thanks to the community of user testing that shaped the tool into what it became, we made the following changes after launch:

1. Added an embed link for others to embed the tool on their sites and in their news articles

2. Added a Favicon for the app

3. Added missing candidate data that was not found in the original dataset

4. Switched the Geocoding query to google places API

5. Updated the ward boundaries using the Open Up Mapit tool

6. Added privacy note on the application stating “The My Candidate tool does not store any user information, including your address.”

7. Added a link to Jodi Allemier’s informative blog piece about how local elections work and what each ballot you receive at the voting stations means.

8. Added the ward number to the search results, making it easier for users to see which ward their street address belongs too.

Future plans for the MyCandidate tool

Open Cities Lab is open to all opportunities to develop the MyCandidate tool further and replicate it in other countries. We are particularly interested in the potential for use in Zimbabwe, Kenya, and other countries in the continent. Whatsapp integration is also on the cards. This would make it possible for users to initiate a request via Whatsapp. And there is also an opportunity More work to potentially create a MyCounsellor type intervention, where we can build a track record for local representatives. We look forward to exploring these ideas and encourage others to contact us about the MyCandidate tool for more information.

Photo: Hennie Stander/Unsplash

Realizing The Promise Of Knowledge Communities

“College campuses are the original “innovation district,” offering a rich density of minds that are concentrated for maximum intake and output of thought. The assumption is always that these minds will meet in serendipitous encounters and campus meeting places. But the reality often falls far short and campuses need to be much more intentional about creating the collision spaces where these interactions can happen.” Phil Myrick, global placemaking leader, lists the many benefits of campus placemaking.

“College campuses are the original “innovation district,” offering a rich density of minds that are concentrated for maximum intake and output of thought. The assumption is always that these minds will meet in serendipitous encounters and campus meeting places. But the reality often falls far short and campuses need to be much more intentional about creating the collision spaces where these interactions can happen.” Phil Myrick, global placemaking leader, lists the many benefits of campus placemaking.

By Phil Myrick, global placemaking leader

Photo: Ruiqi Kong/Unsplash

I visited the University of Texas, Austin recently, and was elated to see how alive and abundant campus life was, centered on a fairly new campus space, the Speedway Mall. It’s a great example of campus placemaking, and captures the spirit of campus life that so many other campuses aspire to.

Campuses are built around the notion of a knowledge community – putting people together to induce the exchange of ideas, not only between student and teacher, but across an intricate network that touches all members. Hopefully.

And yet, it doesn’t always work out that way. Many campuses lack a sense of place and most campuses underrate the importance of the “life between buildings,” treating their public spaces as an afterthought, or as grassy backdrops.

There’s no excuse for this. The reasons for college administrators to make the most of their campus public realm are many and compelling:

Campus Sense of Place and Meaning

Colleges and universities should strive to create vibrant and memorable places that give deeper meaning to campus residents and bring them back years later for reunions, for visits with children in tow, for future giving. Harvard University realized this when they incorporated Placemaking in the master planning of the new Allston Campus. They were aware of the danger that the new campus, although walking distance from the fabled Harvard Yard, would feel like another world with none of the soul and beauty that the older campus is so known for. Harvard continues its work with placemaking on both the Cambridge campus as well as the Allston campus.

Campuses as Innovation Districts

College campuses are the original “innovation district,” offering a rich density of minds that are concentrated for maximum intake and output of thought. The assumption is always that these minds will meet in serendipitous encounters and campus meeting places. But the reality often falls far short and campuses need to be much more intentional about creating the collision spaces where these interactions can happen. Such encounters and casual meetings are much more likely when they are planned for, and the programming that goes along with placemaking is a powerful tool for campuses to use.

Creating Places of Diversity

Planning for interactions must also account for people of different races and cultural backgrounds on campus. In fact, one of the best ways to diversify the groups that gather -- and to make campus places more inclusive – is to target specific audiences who might otherwise not feel welcome. To quote the Brookings Institution: “If public spaces are designed and managed for a monolithic “public” or “average user,” they will likely be exclusionary and fail to achieve their goals of engendering social cohesion.”

Activating Campus Places

There are so many campus spaces that are literally just hardware with limited purpose. To breathe life into a campus, a significant budget should be saved for programming to attract people, enliven campus, improve bodies and minds, and actually put facilities to their best use.

Campus Placemaking

This notion of a knowledge community is an old one – it goes all the way back to the establishment of cities as the most efficient way to capture talent, foster innovation, and grow economies. It applies to university and college campuses, but also research campuses, medical campuses, innovation districts, and other urban districts.

There are layers of social and civic infrastructure that are invisible to most professionals in planning, design, and development. When these layers are overlooked, we miss an opportunity to enrich lives and build community – or in the case of universities, the chance to create a knowledge community that fosters exchange and innovation and builds rich student life. This is where placemaking comes in, and why it’s a valuable addition to campus planning and design.

Photo: Rainhard Wiesinger/Unsplash

Welcoming Locals With The Civic Park Groundbreaking

“The mantra during this entire period has been, roughly, ‘build downtown for locals, not tourists. We’ve been pushed out by the tourists for too long.’ The return of locals only seems right, for what is one of America’s very oldest cities with a totally unique and authentic culture.” Phil Myrick, global placemaking leader, has been a driving force in the transformation of downtown San Antonio into a more welcoming place.

“The mantra during this entire period has been, roughly, ‘build downtown for locals, not tourists. We’ve been pushed out by the tourists for too long.’ The return of locals only seems right, for what is one of America’s very oldest cities with a totally unique and authentic culture.” Phil Myrick, global placemaking leader, has been a driving force in the transformation of downtown San Antonio into a more welcoming place.

By Phil Myrick, global placemaking leader

Photo: Justin W/Unsplash

At long last San Antonio’s new Civic Park broke ground on January 26, 2022. This public-private project will create downtown’s most significant park space and has been called “perhaps the most ambitious development in San Antonio history when you consider the cost, scale and location.” I was thrilled to be able to work with Hemisfair and GGN to help develop the vision for this park.

The initial master plan for this former World’s Fair site, dubbed Hemisfair, was done as far back as 2012, led by Johnson Fain with Olin, HR&A, and Arup. In the following years three public spaces were envisioned and designed, by firms such as MIG, GGN and the Project for Public Spaces:

· Yanaguana Garden, a six-acre mixed use destination playground, was opened to the public for the first time in October 2015 and has come to become the second most visited park per acre in Texas with more than 80 percent of the visitors being locals.

· Civic Park, at 12 acres, is the largest of the three spaces, and will feature civic events like concerts, with tree-lined promenades, fountains and pools, and a perimeter of shopping, dining, hotel and residential.

· Tower Park will mix public space with more than a dozen historic structures, in the last phase of Hemisfair’s development.

Phil Myrick was the placemaking lead on all three projects, helping to establish the overall vision and program.

Tourism and suburbanism

Yanaguana Garden, Civic Park, and Tower Park all have a common thread – and that is to serve and attract local people above all others. For San Antonio, this is a deep-rooted obligation due to the fact that for fifty years the city’s downtown has been mainly the haunt of tourism. The River Walk, a flood project begun under WPA and constructed over a span of decades, eventually became one of the world’s most iconic public spaces. But over time it succeeded especially as a tourist destination, and most locals visit once or twice a year.

Meanwhile, San Antonio’s downtown never recovered from the urban malaise that affected all U.S. cities in the late 20th century, and the city has remained adamantly suburban. For decades, while the River Walk was teeming with visitors, up at the street level the city was a ghost town, characterized by overly-engineered streets that made walking a chore, and an almost complete dearth of retail or residents.

The Decade of Downtown

But, over the last 15 years or so, a devoted and passionate group of city leaders, developers, civic boosters, historians, and most recently the University of Texas, have helped create a surge of investment in making downtown a better place to live. This momentum was given a significant boost in 2010 when Mayor Julián Castro announced his “Decade of Downtown,” an initiative that left an indelible legacy.

Although in 2022 it is still behind the curve (other major cities enjoyed their comeback of downtown many years ago), San Antonio’s downtown momentum has now passed a tipping point. I predict this sleeper of a downtown will soon emerge as America’s latest downtown darling, a success story long in the making.

Build downtown for locals

The mantra during this entire period has been, roughly, “build downtown for locals, not tourists. We’ve been pushed out by the tourists for too long.” The return of locals only seems right, for what is one of America’s very oldest cities with a totally unique and authentic culture. Steeped in a brew of Mexican, Native American, and Texian roots, the city is deeply comfortable with its multiculturalism, and the city has long been majority Hispanic (over 60% Hispanic in the 2020 census).

With this amiable diversity and renewed commitment to downtown, San Antonio represents America’s past, present and future in the best possible way. A toast to the Civic Park, the city’s latest undertaking in a decade of authentic placemaking.

Photo: Henry Becerra/Unsplash

PLACED Academy

PLACED are excited to announce their 2022-23 PLACED Academy. Launched in 2019, PLACED Academy increases participants’ self-esteem, breaks down barriers to professional careers and develops skills. To date, 126 young graduates have benefited from the programme, which has had a positive impact on their lives and shaped their decisions about their future

PLACED are excited to announce their 2022-23 PLACED Academy, their flagship free to access, creative education programme about the built environment for 14-18 year olds from across the northwest, empowering young people to shape the places they live, work and spend time.

Launched in 2019, PLACED Academy increases participants’ self-esteem, breaks down barriers to professional careers and develops skills. To date, 126 young graduates have benefited from the programme, which has had a positive impact on their lives and shaped their decisions about their future

By PLACED

Photo: PLACED

PLACED specialise in place education and engagement. Since 2011, we have brought collaboration and diversity to discussion around the built environment, creating opportunities for quality conversations and genuine engagement. We believe that everyone is an expert when it comes to the places where they live, work or spend time. These principles have been at the core of our built environment Education Programmes for the last years.

Building on our experience, we established the PLACED Academy in 2019 as a free to access creative programme about the built environment for 14–18 year olds. The Academy is designed to increase participants’ self-esteem, break down barriers to professional careers, expose participants to a variety of conventional and non-conventional career routes and develop a broad range of skills. The Academy is made possible thanks to the generous support from our network of Sponsors and Partners.

To date, we’ve delivered four programmes and have 126 graduates. Feedback from previous programmes has been extremely positive; 96% of graduates developed skills that will support them in school, college or university, 92% tell us they now know how the design of places impacts on people, 85% have a better idea of career and education pathways and 80% are more confident they can work in the sector. Reflecting on their experience, one participant told us:

“PLACED Academy is a safe and exciting environment for young people to learn and expand their skills, connections and knowledge, and not only that, but it also provides opportunities which would otherwise be impossible, and many more incredible benefits. The PLACED Academy is one of the best things that has happened to me in terms of my potential future career, and I hope it will continue to aid many other people to gain the necessary understanding of how to get to where they want to be in the architectural, landscaping, interior design or engineering fields.”

We are now in the early stages of developing the 2022-23 programme, where will recruit up to 40 young people from diverse backgrounds from across the Northwest. Academy participants will take part in creative design workshops which respond to live projects, supporting youth voice and citizenship, whilst enabling designers and decision makers to engage with a group typically under-represented in discussion about places. Students will be mentored by industry professionals and participate in a tailored package of workshops, events and learning opportunities, working towards their graduation.

The programme will include the following: