Caracas: Like No City In The Western World

“Despite setbacks, working in Caracas was a useful wake-up call. It raised the fundamental questions that we believe planners and architects must respond to in the 21st century: How does one deal with chaos and with the sudden and unforeseen shifts in the political climate? How do we respond productively to the particulars of time and place and to the problems of population growth and migration? If disorder and antagonism are the status quo, how do we exercise a discipline that imposes order and requires consensus?” Alfredo Brillembourg, architect and founder of Urban-Think Tank, explores the dense urbanism of Caracas in the light of some of the Western world’s most urgent challenges.

By Alfredo Brillembourg, architect and founder of Urban-Think Tank Design Group

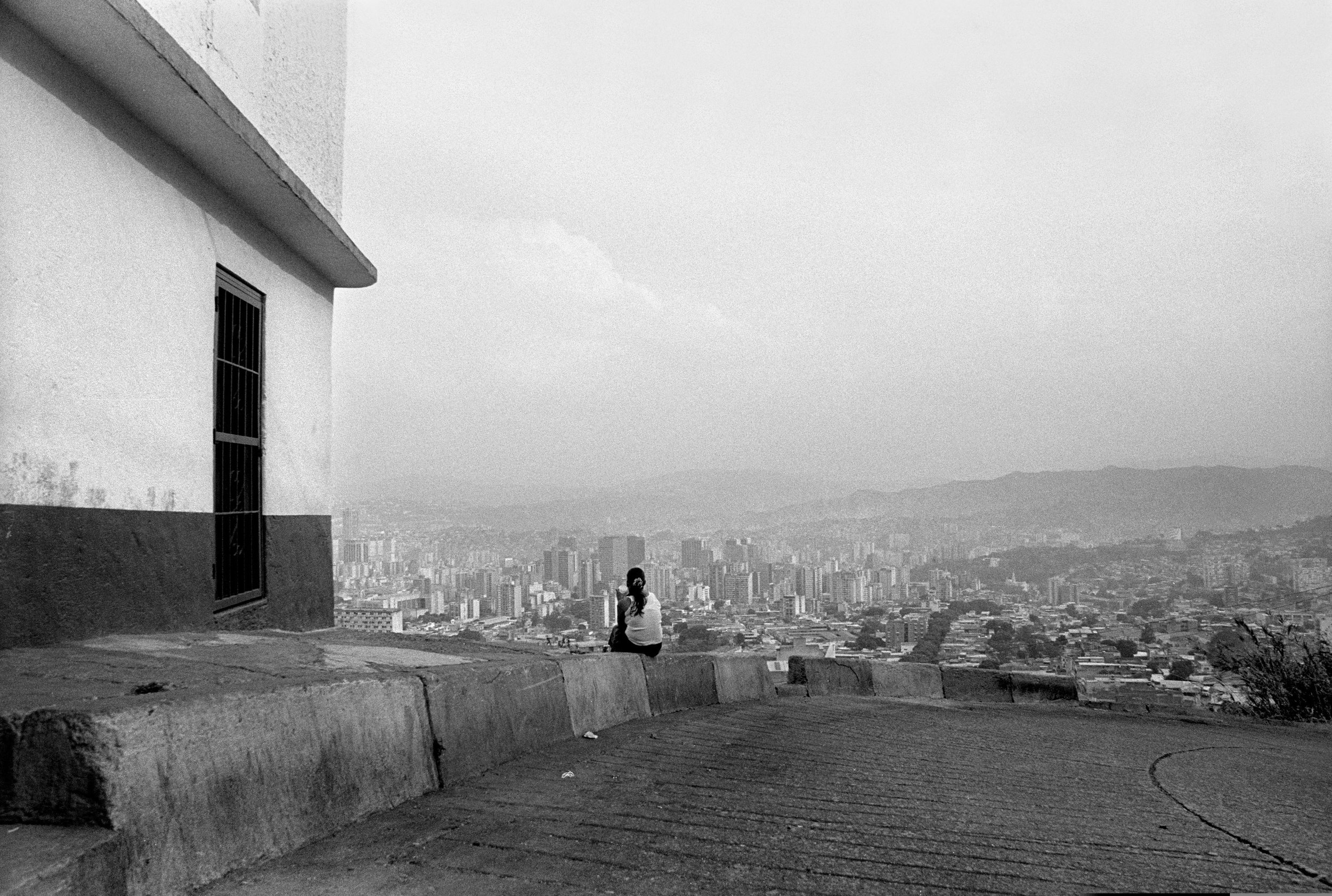

Photo: André Cypriano/Urban-Think Tank - Caracas Case

Think of Caracas today as:

A city 1000 meters above sea level, in a 20-kilometer-wide valley,

A metropolitan area of 800 square kilometers,

A regional population of approximately 6 million, in a country where

more than 3.3 million Venezuelans—approximately 10 percent of the population—have fled the country in the past four years.

A maximum density of 573 inhabitants per square kilometer,

A built area of 50% informal settlement,

A community spending over $1 billion per year on private security,

A population that produces 4,000 tons of solid waste daily with no recycling plant,

A settlement with a permanent water shortage,

A territory with no common political base, consisting of five distinct municipalities sharing territory in three different states,

A country with a 10,000,000 % inflation rate

A place where gasoline is cheaper than water,

A place where 75% of the population has lost an average of at least 20 pounds in 2019 due to a lack of proper nutrition amid an economic crisis.

A society where more people live, work, and die in the informal city than in the formal part of the city,

Think of … “Blade Runner” in the Tropics

Informal Capital

Caracas has grown to dimensions unanticipated by planners a decade ago. Informal urban sprawl expanded the city to the east, covering an area four times larger than the city’s 1950s metropolitan boundaries – a growth limited physically only by the mountainous topography. East to west, the boundaries of metropolitan Caracas are 60 kilometers apart; north to south, the city stretches some 20 to 30 kilometers. Since 1967, the built area has nearly doubled, to some 900 square kilometres. While it is difficult to anticipate future patterns of expansion, we do know that today approximately one million families live in barrios. How many will there be in 2030? Where will they live?

To the extent that Caracas is known to the world at large, people are primarily aware of Venezuela’s crisis wrecked by hyperinflation, severe food and medicine shortages, soaring crime rates, and an increasingly authoritarian executive. In 1970, Venezuela had had a staggering economic growth for 50 years, but now as thousands of citizens leave, Latin America is seeing one of the largest refugee crises in its history. Venezuela's outpouring of refugees is only second to that of Syria. Six million Venezuelans have escaped their homeland since 1998.

Photo: André Cypriano/Urban-Think Tank - Caracas Case

If Architecture is Frozen Music, Urbanism is Frozen Politics

Both in its successes and its failures, Caracas exemplifies the ways in which cities are shaped and eroded by the explosion of laws, regulations, and agencies, and it illustrates the deplorable results that often result from good intentions when the middle-man is the government. In the 1920s, Caracas, was among the poorest cities in Latin America; but by the 1950’s it was the most prosperous city, with the most modern infrastructure of Latin America. Petroleum was the motor of this economic miracle, giving Venezuela 15% of the world petroleum market. Despite the 1950’s dictatorship, Venezuela chose a progressive capitalist mode of production, which promoted prosperity and economic freedom. The results were reflected in the upper class’ emulation of North American standards of life and in the stature of Caracas as a major metropolis.

After 1957, however, Venezuela confused democracy and development with socialism, in a reaction to the capitalism of the previous regimes. Governments from 1958 to the present have pursued a policy of populism, under the guise of social democracy. Venezuela’s political and economic system during the second half of the 20th century substituted private investment for public expenditure, and the state government became the principal employer. Furthermore, during the ‘60s and ‘70s, Venezuela slowly began to lose world market share, dropping to just 3% in 2002 [1]. Not surprisingly, the consequences of the country’s economic down-turn have been social crisis and the proliferation of barrios.

As Caracas’ rich became richer, housing prices rose, pushing the urban poor to the city’s fringes and into abandoned buildings. With the complicity of a weak government, the wealthy effectively promote sprawl, which, in turn, raises the cost of such services as transportation, water, and electricity. With each cycle of development, the barrier between rich and poor grows higher, segregation more intractable, and economic distinctions more pronounced: approximately 75% of Venezuela’s poor are urban dwellers.

All social classes in Caracas suffer from similar difficulties: lack of essential services like shops, schools, and hospitals; enormous distances between home and work, complicated by nearly perpetual grid-lock; unregulated work hours. But the problems are significantly greater in the barrios which have neither institutional buildings nor services: no postal delivery, no trash or wastewater collection, no supply of potable water. Electricity is almost exclusively “stolen.” There are, of course, no paved roads.

The Code of No Code

Unregulated urbanization has become the most significant, if misunderstood, force in the development of Caracas. On the one hand, official maps of Caracas until recently indicated the location of the barrios with blank white spaces, erasing them from formal recognition. On the other hand, the barrios of Caracas represent the largest illicit collective initiative and infrastructure built in South America. Consider, for instance, that between 1928 and 2004, the government managed to build only 650,000 units of public housing. With no government assistance, inhabitants of the informal city have themselves added 2.8 million squatter homes in the same reference period.

These settlements are both illegal – the squatters, by definition, lack title to the land – and extralegal, since existing zoning codes have no jurisdiction over building sites that lack any title of ownership. But the squatter cities are not without their own codes, following unwritten rules of self-organization. Despite the poverty, illegality of the settlements, and lack of property ownership, the informal city is a vital example of a free and creative housing market. The inhabitants have entrepreneurial skills, enthusiasm, and an astonishing ability to wring a profit out of practically nothing. The invention and commercial activity of these informal settlements strongly suggest that the poor are economically progressive and free-market oriented.

Photo: André Cypriano/Urban-Think Tank - Caracas Case

If the urban sprawl of the barrios appears chaotic, closer scrutiny shows clear criteria of purpose and economy. Indeed, they make a valid argument for self-organization and independent construction. The barrios are, in effect, a complex adaptive system, permanently recreating itself and open to all forms of adaptation. Structures are generally equal in size, employ the same materials and construction techniques, and differ little in style and decoration. Though conceived by an individual, each building is a component in an inseparable whole, a cell in the system of the barrio. The unofficial roads, stairs, and passages through the barrio create networks that bind the whole together, creating an internal logic that works well for its creators and knitting a myriad of small, overlapping communities into a large informal city. In the absence of architects or other professionals, the structures are nonetheless rational in form and method.

“In the absence of a conventional master plan, the barrio-dwellers have put their talents for organization, improvision, and inventiveness to the development of a mega housing project for 42% of the population of Caracas.”

Non Transit

Caracas - with the exception of the barrios - is a car city. Trains and trolleys have been destroyed; sidewalks are nonexistent, and walking on the street is difficult and dangerous. The oil-based economy inevitably favored cars, which, in turn, required a network of massive highways. The U.S. highway system, initiated in the ‘50s during the Eisenhower administration, was the model and ideal, imported to Caracas in the late 40’s, as the embodiment of progress and good government. In 1948, Robert Moses, New York’s chief planner and master builder, arrived in Caracas and proposed a new urbanism of highways. Moses, not only laid out the highway program in Caracas, but the program profoundly influenced the living conditions and changed the landscape of the city. The imposition of the Caracas Freeway system played an important role in the fragmentation of the post-colonial city. These roads arbitrarily and irrevocably separated entire communities. If you build it, they will come: building a freeway in a large city increases vehicular traffic; more highways or added lanes bring more vehicles.

Photo: André Cypriano/Urban-Think Tank - Caracas Case

Today, Caracas’ highway system resembles that of Los Angeles, and to similar effect: driving suburbanization and sprawl to the detriment of countryside and city. While Caracas inaugurated a subway system in the ‘80s as an alternative to the car, it is heavily used by commuters from the barrios. And in consequence, these commuters have flooded the city creating new informal markets around subway hubs and underneath the freeway structures in the city center.

Restoring the Ruins of Modernity

The cities of the world have each had their respective eras of wealth, major development, and great architecture. Barcelona grew to its unique form under Cerda in the 19th century, Vienna had its great expansion in the beginning of the 20th century, and Caracas had its moment in the 1950´s. Today in Caracas, the great architecture of that period is either in ruins or steadily decaying. Even as we make the case for the future of Caracas – for the value of the informal, the barrios, the unacknowledged structures and systems of the city – we argue, too, for preservation of its history.

We would like to recall the history of Caracas, where heights of city buildings rose from one to some twenty floors in about five years in the economic boom of the ‘50s. The lessons learned from revisiting boom-cities of the past like Caracas, Detroit, Glasgow, Berlin or Beirut can be invaluable. Cities never die, but often fall in and out of the spotlight rapidly.

Caracas has forgotten, if indeed it ever fully recognized, that it is home to exceptional and unique works of architecture, Roberto Burle-Marx’s metropolitan park, Wallace Harrison’s Avila Hotel, Gio Ponti’s Villa El Cerrito and Richard Neutra’s Gorrondona House among them. The recent designation by UNESCO of Carlos Raul Villanueva’s Universidad Central de Venezuela UCV as a World Heritage Site has called world attention to the city’s cultural treasures and to their ruinous condition.

Will this attention last, and will it make a lasting contribution to the preservation of modern architecture in Caracas? That remains to be seen. A great number of the 100 historic cities and nearly 200 sacred sites on the World Heritage list are located in the Third World, in countries whose limited financial resources make preservation a very low priority. Caracas and Venezuela overall are no different in that respect.

The historic central area of Caracas requires most careful study, not only for the architectural significance of many of its buildings, but their problematic counterparts: higher population densities, an active and large informal economy, and total traffic congestion. Some 250 thousand people and 50 thousand cars circulate daily through 9 city blocks immediately surrounding the Congress building in central Caracas, an area that is also home to 18% of all informal commerce in Caracas. The result of this confluence is the continuing erosion of property values in the city center and, as a corollary, decay of historic structures, problems that should be addressed and resolved. Traditionally, architects and urbanists have held that the preservation of cultural heritage and reduction of poverty are linked. If that principle still holds, then for Caracas and for similar cities around the world, we need new approaches to preservation that account for the realities of urban development in the 21st century.

How does one urban development affect the meaning of another when their diverse expressions are combined and how can the dynamics of informal urban developments contribute positively to the city?

Photo: André Cypriano/Urban-Think Tank - Caracas Case

Caracas: A 21st Century Cold War City

The only way to begin to grasp the singularity that is Caracas is to chart its post-WWII trajectory till now. It might disappear from flight maps by the middle of the 21st century due to political collapse and hyperinflation, but two decades ago it was a place of destination. Caracas is only four and half hours from New York City, the place where I was born, but the truth is now it is somewhere else.Many Caracquenos, as locals are called, have left the country. With the exodus of 5000 Venezuelans per day, Caracas is a shrinking city and a shadow of what it used to be. Don't get me wrong, the city is still there, the Avila mountain still stands tall in the Valley but the city is caught in a new proxy war similar to what happened in Havana, Cuba in 1964. Instead of Cold War I would call it the “slow death” of a country, and the political crisis is leaving indelible traces on the city of Caracas, where polarities on the global stage crystallize and intersect with political and social dynamics run by Cuba and Russia. It is a slow death for the city because there is no large-scale fighting directly between the two local opposing sides, but they each are supported by major regional global players, and the stage for this proxy war is the city.

If we look back, in the 1970s, Caracas was the hub for South America. Like Dallas’ oil barons, its newly rich businessmen met and made their deals at exclusive establishments, such as Le Club[2]; like their Parisian confréres, the intelligentsia of Caracas sat in cafés and discussed art, wreathed in the smoke of their cigarettes; and like the glitterati of Los Angeles, the Telenovela stars hid from paparazzi behind dark sunglasses. All of the continent’s power elite seemed to be concentrated between the hills of El Ávila and the river. The valley of Caracas was like New York City in Saul Steinberg’s famous map: everything beyond the city limits receded into tiny specks, while the picturesque Boulevard de Sabana Grande, with its cafés and upscale international stores like Cartier and Saint Laurent, occupied an oversized swath of the public imagination.

Now, nothing prepares the traveller from North America. When you walk out of Caracas’s Simón Bolívar Airport, you are hit by a degree of heat and humidity you can’t have imagined. Here at sea level, you might as well be in a sauna; only in the hills does the air become tolerable. It is a fantastic experience to make the transition from the familiar to the completely, overwhelmingly different: the sea, the sounds, the smells, the cars, the vegetation. To travel from New York City to Caracas is an even greater shock than it once was to cross the Iron Curtain into the socialist eastern bloc. Nothing prepares you for Caracas.

Photo: André Cypriano/Urban-Think Tank - Caracas Case

On the streets of Caracas today, the decibel levels are higher than we could have imagined. Honking—a practice that frowned upon, if not entirely forbidden, in North America and Europe—is just an expression of the driver’s mood and circumstances. There are happy honks, “I love you” blares, and little diddles when the driver turns into a parking spot[3]. Diesel and wood smoke assault you as you drive from the airport down the narrow valley where half of the nearly six million Caraqueños live stacked in towers and still others in hillside shacks called ranchos.

Conditions began to change with the election of Hugo Chávez in 1998. It wasn’t an explosive revolution, not like Tehran in 1979 or Saint Petersburg in 1917. The changes were gradual, like the rising temperature of the water in which the frog is placed: the initial warmth is deceptively comfortable[4]. Even insiders welcomed the reforms to a system that was sclerotic and dysfunctional. But within a few years after the election, the country was working itself into a rolling boil: a democratically manipulated dictatorship.

Chávez had come to power promising to disrupt the old ways, the “natural order of things”—what and how Venezuela had always been. There was a relatively small crowd of people with money, educated in world-class schools, who tacitly, even reflexively, affirmed the order of things. Caracas’ upper levels of society lived in houses in neighborhoods called Country Club, Valle Arriba, and La Lagunita; the poor worked in the kitchens and gardens, living in the barrios embedded in the city and sprawling up the hillsides.

Historically, barrios urbanos , what American’s call slums, were not considered a recognized part of Caracas. Official maps of the city showed the barrios as generous green reserves or blank spots on the map, even though seventy percent of the modern city is made up of informal shelters draped over the mountains. Even in the 1990s, politicians did not see the masses located in these areas as fully human, enfranchised Caraqueños, but as cheap labor. The barrios and their residents were a problem, best ignored—out of sight is out of mind, after all. The formal city was the only Caracas.

Of course, there were people who acknowledged and investigated the informal city: planners like Teolinda Bolívar, whose 1970 doctoral thesis at the Sorbonne cast light on the topic; architects like Federico Villanueva[5] and Josefina Baldó, professors of architecture at the Central University of Venezuela; and architectural historians like Oscar Olindo Camacho, who took a humanistic perspective on Caracas’s barrios. Others were anthropologists and sociologists. But their work, while creating a valuable foundation, consisted almost exclusively of statistics and inventories.

In the late 1990s, Consejo Nacional de la Vivienda (CONAVI) and a small team divided the sprawling informal swaths of Caracas into areas that could be quantitatively mapped and charted, so as to propose and evaluate development projects (partially funded by the World Bank)[6]. Here, too, the approach is useful, but we found it incomplete. We wanted to connect the social science research with the world of architecture and aesthetics and with action and intervention.

Actors on the ground—the barrio residents—were constructing the city without any awareness of or reference to theories and measurements and academic knowledge. They simply built what they needed when they needed it, using whatever they could scrounge. It was enormously important to us to understand the dynamics of these processes and to identify the embedded principles so these could be applied constructively to the empty spaces, borders, and holes in the urban fabric[7]. And we sought ways for common individuals, community leaders, researchers, and formally trained architects to come together to create new projects for those spaces, hoping that our work would slice vertically through the complex layers of city-making. All of this—the inquiries and research and relationship-building—was the creative wellspring for the efforts that would engage me for years to come.

Built around a colonial-era village with a stunning pink eighteenth-century church, Petare is home to established informal communities knit together by a dense network of hillside lanes, stairways, arches, and chutes. With a strong social network and cultural connections, it is home to thousands of micro-businesses that recycle materials, make handcrafts, and produce many kinds of food. When we came down from the aerial surveying, we realized we needed to learn about this community if we wanted to understand our city.

A popular tale has it that the mega-slum of Petare was born during the construction of the 23 de Enero Housing Development in the 1950s. Those displaced by the construction were promised new apartments in the eastern Sucre Municipality. But, as one Petare old-timer, Oscar Genaro[8], told us, “When we arrived we found only long grass and snakes.” He and his neighbors built their housing around the cathedral. In the years since, this peripheral site has been enveloped by a city hungry for land. This urbanizing initiative, though it would not be recognized as such by urban planners, created one of the largest communities in Latin America.

Saying that Caracas ran is really giving it too much credit: at this point, it barely sputtered along. The booming Caracas of the 1940s through the 1980s had slowed down and stalled out. In the 1950s, General Marcos Pérez Jiménez had run an ambitious modernization campaign. His government poured millions of liters of concrete into the Caracas valley to modernize the economy and build public works to rival those of North American cities[9]. Jiménez built huge roadways and started grand modernist housing schemes like the 23 de Enero Housing Development[10]. The infrastructure behind Caracas’s boom years also helped to disable it: although the wide boulevards, imported automobiles, and stacked interchanges initially helped facilitate the movement of a new class of entrepreneurs, eventually it made for a city with insane traffic jams, smog, and muggings. For a lucky few, among whom we must include ourselves, there was still a way out of the tangle of the city: the airport.

“In the developing world, the airport still serves the same function as Star Trek’s transporter: it beams you to another universe—or at least up out of whatever mess you are in. ”

You go to the airport, insert yourself into a metal tube, and emerge in a place where life is easier—where tap water was safe to drink, where car jackings never occur, and where automobiles need not be bulletproofed.

Photo: André Cypriano/Urban-Think Tank - Caracas Case

Everybody Has an Agenda

In 1998, the Venezuelan people, tired of a two-party regime rife with corruption, whose policies created and perpetuated insupportable social inequalities, voted Hugo Chávez into power. Much more than a just a populist, he was welcomed as a redeemer. His skill at and addiction to the persistent use of media were no small part of the persuasiveness of his message. “Alo Presidente,” his weekly live television program, was reality TV and soap opera at the same time. There was a dark side, of course, that became increasingly disturbing to many Caraqueños, who encountered the militia groups, enforcers of Chávez’s policies, and his “collectivos.” The latter were especially vicious: motorcycle gangs made up of ex-police officers and thugs. Although they were nominally autonomous, there was never any doubt that they were carrying out the government’s policies and edicts, as well as pursuing their own agendas. Among these was Lina Ron, perhaps the most faithful Chavista. Her enforcement of Chavismo was a form of street justice in which laws and lawlessness, far from being antithetical, are conflated.

Lina Ron was, and remains, a legend and folk hero among these gangs who spread terror throughout the city, even among the urban poor of the barrios, who most strongly supported Chávez’s version of socialism. She may not have looked much like an enforcer—short in stature and with masses of dyed blonde hair—but she certainly played the part: roaring into a neighborhood on her unmufflered motorcycle or in a Jeep with no license plates, accompanied by her tough-guy crew who had a penchant for cracking heads. A typical headline in the Caraqueño press of the early-2000s would read “Lina Ron” followed by “shots fired” or “sped away.” In our one encounter with her, she looked exactly as she did in the tabloid photos: red baseball cap, tight top with a low décolletage, a mobile phone wedged between her breasts, and a gun at her hip. She was María Lionza[11] gone rogue. At the height of her fame in 2009, she was symbolically jailed for three months for leading a violent attack on the offices of the pro-opposition television station, Globovisión.

Other fervent Chavistas worked to equal effect within the system, some adamant in their stance, others bending with the prevailing political wind. Even when we enjoyed influential support, our way forward was blocked by the will and power of the party.

Venezuela is an oil-rich state, and Caraqueños love their cars. The post-war building boom included vast ribbons of roadway, including the elevated highways that make Caracas—at least at a distance—resemble Los Angeles. Few roads of any size or condition reach the barrios, whose residents, in any case, very rarely own cars. The city does have a subway system, but given the steep incline of the hills, it stops short of the barrios.

Around the turn of the millennium, the city advanced a scheme to build a roadway to serve the barrio of San Agustín. It was a politically astute choice: close to Caracas’ central business district, with a formal street grid, and, at the time, relatively safe. The project would be an easy, highly visible win for the new Chavez government and a way to demonstrate the fulfillment of campaign promises.

Fortunately, unlike the seizing of private property, major infrastructure projects in Caracas unfold slowly. This gave us time to investigate the impact of the government’s plan and, more important, to spend time with the residents of San Agustín, encouraging them to voice their opinions and to tell us what they did and didn’t want. From their point of view, and ours, a roadway would destroy their community, physically and socially; our research showed that it would obliterate more than thirty percent of the houses in the barrio and tear its fabric in pieces.

Photo: André Cypriano/Urban-Think Tank - Caracas Case

The Closer You Get, the Worse the Smell

The beginning of the twenty-first century saw once again the rise of the “strongman”: Vladimir Putin in Russia, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Turkey, Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, and—notwithstanding a tripartite arrangement of checks and balances—Donald Trump in the US. They all rose to power as game-changers: Erdoğan championed the increased political participation of observant Muslims; Chávez proclaimed the rights and supremacy of Venezuela’s poorer citizens; Trump announced his intention to “make America great again.” Democracy would triumph.

But ego is a strong incentive. In pursuit of power and acclaim, Chávez steamrolled the opposition, both within Venezuela and in the rest of the world. At the same time, he charmed, at least initially, a large segment of the international Left. The farther one went from Venezuela itself, the easier it was for him to pull the wool over the eyes, especially those of North American and European intellectuals, who saw only what looked like an amazing revolution and a glorious future. For those of us who lived through the early 2000s in Caracas, spending time in left-leaning circles in the US, especially with our Columbia friends in New York, was at best disconcerting. At worst, dinner party conversations turned into shouting matches.

Times have changed, of course, and so have opinions. Under Chávez’s chosen successor, Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela has sunk into a swamp of corruption, mismanagement, and an economy in crisis. The currency is all but worthless, the opposition jailed, and the very people Chavismo was supposed to benefit are rioting against the government. Maduro and his United Socialist Party nonetheless hold onto power by using the authoritarian measures beloved of all strongmen. When all else fails, they follow the example of Chavez: writing a new constitution and sidelining the opposition-controlled legislature. Venezuela has become a pariah among nations.

Despite setbacks, working in Caracas was a useful wake-up call. It raised the fundamental questions that we believe planners and architects must respond to in the 21st century: How does one deal with chaos and with the sudden and unforeseen shifts in the political climate? How do we respond productively to the particulars of time and place and to the problems of population growth and migration? If disorder and antagonism are the status quo, how do we exercise a discipline that imposes order and requires consensus?

We didn’t have all the answers for dealing with the complex political, social, and economic realities of Caracas. But we did learn that, to effect any change at all, our guiding principles must favor integration over analysis, relationships between things over things themselves, growth and change over stasis. Still more important, we recognized that the architect cannot rise above the fray, aloof and in isolation from conditions on the ground. To have any hope of real accomplishment, we must school ourselves in politics, economics, and sociology; we have to understand the forces that propel tectonic shifts in the fabric of a city.

During our years in Caracas, simple survival became an increasingly pressing issue. The economy suffered from hyperinflation and the plunging devaluation of the currency; Venezuela had no budget for quality infrastructure projects. Construction materials grew scarce. Drinking water was more expensive than gasoline, and it was easier to procure a bullet than a roll of toilet paper. Spurious charges we leveled against opposition leaders, who were then jailed, some for years on end. Protests were met with tear gas, bludgeoning, and bullets.

2002 was a watershed year for the city and for us. In April, during mass protests against the Chavez regime, twenty people were killed and more than 110 were wounded. Chavez was removed from office for 47 hours, returning to power stronger than ever. That same year, he “reformed” the national oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela S.A. (PDVSA), by appointing political allies to head the company, replacing the board of directors with loyalists with no experience in the oil industry. Whereas the take-over of the Metro Company was politically inconsequential, this seizure led to a two-month strike. The government responded by firing some 19,000 striking employees for abandoning their posts. They were replaced by foreign contractors and the military.

Falling Towers[12]

In the 27th episode of the American television series, “Homeland,” Torre David is emblematic and headquarters of a Latin American, Islamic, narco-terrorist group. That conflation of affiliations is matched in the episode by the juxtaposition of the call to prayer at the largest mosque in Latin America and a mural of a heavily bearded Chávez. In the series, the tower is both refuge and prison for the character of former US Marine Sergeant Nicholas Brady, on the run as a wanted Al-Qaeda terrorist and hiding among the villains in the apocalyptic tower. Once again, Latin Americans around the world went ballistic, as they had over our exhibit. But this time, they had some justification: the parallels between “Homeland” and the real community living in Torre David are superficial at best. Then again, it should be said that “Homeland,” like the telenovelas, is fiction.

As it happens, the real leader of the Torre David community, Alexander “El Niño” Daza, is the clean-cut pastor of an evangelical church located in the complex. Although he occasionally carries a gun, he is more likely to be holding a bible. In his article, “The Real ‘Tower of David’,” Jon Lee Anderson notes that “in ‘Homeland,’ there is no escape from the Tower of David,” while in real life people come and go daily through the gated entrance. In both articles—his earlier one was “Slumlord”—Anderson gives a terrifically insightful and incisive account of the socioeconomic and political drama in which the tower and its inhabitants are enmeshed.

For four years following the Biennale, we persistently, and unsuccessfully, lobbied the central government of Venezuela to allow the Torre David residents to continue to occupy and improve the tower. We even presented our detailed proposal for completing the tower in ways that were appropriate to the community, its limitations and its needs. We had in mind a cooperative housing scheme—essentially what already existed, supplemented by outside support and assistance; but the tower was far too valuable a piece of real estate, given especially its location. And the government of Nicolas Maduro needed to implement Chávez’s “Great Mission Project” of providing public housing for former slum-dwellers, to demonstrate that it was capable of fulfilling its promises.

The notoriety that our exhibit created for Torre David was a two-edged sword: as much as it drew attention to Venezuelan politics and to the plight of the unhoused, it also made it impossible for the government to sit on its hands forever. We knew, and the community knew, that all the visibility and debate would likely lead to eviction. Still, the community leaders hoped that they would not simply be thrown out onto the streets, but relocated to a new—and better—home. Finally, in 2016, the housing authority began moving the Torre David residents. The conditions in the new public housing was indisputably a considerable improvement. But from the point of view of the residents, there are two significant drawbacks. Some of the new locations among which they are now scattered are as much as 70 kilometers from central Caracas. Many of the new developments have no source of jobs, so residents commute daily, having to rise early to catch a 5:30 a.m. train and returning home very late. Still others have no supermarkets or secondary schools.

At least as important for the residents is the loss of community. Over the course of nearly a decade, the squatters, refugees from the barrios, had created order and security. They created their living spaces according to their respective choices and needs. Theirs was a cooperative and communal way of life, something their new neighbors neither knew nor appreciated. They lived in the middle of Caracas, in the midst of the messiness and liveliness they understood. Their lives in Torre David may have been precarious, physically and politically, but the tower was home.

When they are completed, skyscrapers often garner international recognition; their demise is rarely noted. Today, Torre David is empty. The government talks, with misplaced and spurious optimism, about redeveloping it as a cultural office complex. Meanwhile, the country suffers from hyperinflation, food insecurity, lack of medicine, political instability. People are fleeing the country, if they can; they are dying if they can’t. Poverty is endemic. The government’s approaches to the housing crisis—evictions, slum-clearing, relocations—have only exchanged one problem for another. What distinguishes Torre David is its representation of an alternative social reality that was enabled by the very fact of government abandonment and willful neglect.

We believe that the story of Torre David, from ground-breaking to desertion, offers a valuable learning experience. It advises everyone to ignore the simplistic extremes beloved of the media and of critics: we found that the tower is neither a hot-bed of violence and disorder, nor a romantic utopia. It does not represent the good or the bad, what should or should not be—it just is. An empty, incomplete building, it is a constant reminder of a deepening housing crisis, economic breakdown, and the unfulfilled promises of a government more interested in remaining in power than in improving the conditions of the people it purports to represent.

Torre David had the complexity of a city, compressed into an unprecedented, vertical format. It combined formal structure and informal adaptation to provide useful, appropriate solutions to the urban scarcity of space. It defied everything we ever learned about architecture and urbanism. We should not mourn its abandonment. The point was never to preserve what was improvised and destined to be temporary. One building should never be viewed as a panacea or an ideal model for architects to emulate. Everything depends on context—geographic, economic, political, cultural, chronological. The questions are global, the answers are local. There are many Torre David’s scattered around the world. Architects need to study and learn from each of them.

Thinking About The City

For much of the past 20 years, our research and design work has primarily concerned relatively discrete interventions: individual structures, from the vertical gym to Torre David; connective tissue, such as the cable car and the Avenida Lecuna metro; and neighborhoods, like Hoograven and Khayelitsha. But all the while, we were thinking and talking about the city, about what urbanism might mean and be in the 21st century. The rigid separation of formal and informal, planned and ad hoc, wealth and poverty, made no sense to us. Those distinctions are inherently unstable politically, economically, and geographically; marginalization is a social and physical phenomenon, a kind of illness afflicting the civic body.

Photo: André Cypriano/Urban-Think Tank - Caracas Case

The disconnect between formal and informal has at least two root causes. One is organic: cities grow outward, like the ripples in a pond when one drops a pebble in the middle. Like the ripples, the encircling neighborhoods grow weaker and less coherent the farther they are from the center. The other cause follows the law of unintended consequences: infrastructure, especially transportation, creates barriers between the haves and the have-nots, in the interest of improving vehicular movement. One sees this especially in the older US cities, like New York and Chicago, but also in the ring roads of cities like Rome, which inhibit migration. Even where public transportation and pedestrian bridges provide access across highways and six-lane boulevards, neighborhoods are still cut off from one another, preventing mingling and sharing.

“Just as we see verticality as a way of addressing the need for more residential space in the barrio, we also believe that the failure of conventional city planning lies in its two-dimensionality, its tendency to think only in a single, horizontal layer.”

At best, one finds an underground metro, connected to but not interlaced with the street level. What if, instead of burrowing underground, we were to build a new city on top of the existing one? What if we made multi-level interconnections, increasing density and relationships? Of course, this is a utopian vision, and we live in the real world. But utopia is like zero-defect manufacturing: you have to act as though it were possible, in order to make any progress at all.

And so we ask: if the city as we know it didn’t exist, what would we invent? “The city was not prepared for the people and the people where not prepared for the city.”[13]

Although the barrios of Caracas have managed themselves, in the absence of local official government, and have done so reasonably well, the fragmentation of the city administration overall is a major obstacle to progress. The authorities operate in a state of perpetual crisis: services and maintenance are lax at best; public employees go for months without pay; having “legitimated” the poor by enabling them to vote, the government continues to ignore poverty itself. The poor have given up on the promise that the barrio would be a way-station to a better life and have settled in for the duration.

The problems besetting the barrios cannot be solved independently of those from which the entire city suffers. Several municipal planning officials each told us independently that no joint projects can be realized among the five municipalities. The sidewalks in one borough terminate at a highway on-ramp in another. When one crosses the line from one municipality to the next, rather than a sign of welcome at the latter, at the boundary of the former one reads, “You are now leaving a secure zone.” Tax revenues are municipality-specific: commercial centres and banks cluster in the smallest municipality, which claims their tax moneys, while other boroughs simply fall apart. Each administration’s mandate is limited to an island within the city; there is no incentive to initiate cooperative endeavours with others. The creation of the Metropolitan District of Caracas[14] with its own mayor has proven an empty gesture.

Many in the various city governments are people of good will, but the ostensibly insurmountable obstacles in the path of change and improvement have defeated them. Most significantly, they lack the skills and knowledge to analyse and address the innumerable management, technical, and social problems they face; at best, they conduct a holding operation, trying to keep chaos at bay.

The View From Here

When we were still based in Caracas, we wrote what we called the No Manifesto. We were angry, disappointed, maybe disillusioned as well. The political and social conditions in Venezuela were intolerable, and we called for resistance and change by our colleagues. We embraced the notion of the architect-activist, but everywhere we saw obstacles the impeded transformation and progress.

Photo: André Cypriano/Urban-Think Tank - Caracas Case

Today, we have a complicated perspective. To be sure, conditions in Caracas are worse than ever with a 10,000,000 % inflation rate. There are two paths Venezuela can go down, one, an optimistic path of political transition with economic stability and the other a more realistic one of total collapse and dysfunction. But elsewhere in Latin America, as in cities and countries around the world, we see reasons for hope There is a tremendous amount of work to be done and as yet no broad consensus about how to shape the future. Nevertheless, I believe in that future, and I believe that architects must take the lead. Even If I have moved, in practice and in principle, from the margins of Caracas to the center of the world, I took Caracas with me; Caracas is everywhere, and we all are global architects.

[1] see Andrés Sosa Pietri, Venezuela y El Petróleo, Editorial La Galaxia, Caracas 2002

[2] Le Club is a high society bar created by El Catire Fonseca.

[3] Of course, honking is not exclusive to Caracas. In Mumbai and Delhi, for instance, it’s not only deafening, but actually required.

[4] In a much-cited experiment, a frog is placed in room-temperature water which is then heated gradually until it reaches a boil. Because the rise in temperature is consistent and slow, the frog doesn’t notice the impending danger and, instead of trying to escape, sits quietly until it is boiled to death.

[5] co-author of Premio Nacional de Investigacion en Vivienda. Caracas, 2008.

[6] See the Caracas Slum Upgrading Project, http://web.mit.edu/urbanupgrading/upgrading/case-examples/ce-VE-car.html.

[7] These areas, defined by Catalan architect and theorist Ignasi de Solà-Morales as terrain vague, are shifting entities that respond to a variety of internal and external pressures. They are places where top-down meets bottom-up and vice versa.

[8] Oscar Genaro was introduced to us by Teolinda Bolívar.

[9] Among those works in the U.S. were such initiatives as Eisenhower’s Interstate Highway System and huge public housing projects like Chicago’s infamous Cabrini-Green. In New York City, Robert Moses’ urban renewal scheme required the razing of an entire district of tenement houses and the displacement of its residents for the construction of Lincoln Center.

[10] Originally named Urbanización 2 de Diciembre for the date of Jiménez’s coup, it was completed and renamed by his successor for the date of the former’s removal from office.

[11] María Lionza, the central figure in the Venezuelan religion that blends African, indigenous, and Catholic beliefs, is revered as a goddess of nature, love, peace, and harmony.

[12] T.S. Eliot, “The Waste Land,” 1922: What is the city over the mountains/ Cracks and reforms and bursts in the violet air/ Falling towers/ Jerusalem Athens Alexandria/ Vienna London/ Unreal.

[13] Luc Eustache, CAMEBA Project Architect, Informal Conference UCV/CCSTT, 2003

[14] Special Law for Metropolitan District .Oficial Publication No. 36.906 ( Regimen del Distrito Metropolitano de Caracas Gaceta Oficial)